In the art of Byzantine iconography, the various saints of our faith are depicted, as well as various representations that have to do with religious subjects. It is an art that has to do with the spiritual world and that aims to unite it with the physical world.

The forms are altered, but given their basic characteristics, and we have shapes and colours, in a spiritual dimension and in combination with the simplicity of the images, the message of simplicity and symbolism that the pictorial representation brings out is given, to go on the journey them through the centuries.

The objects painted in iconography acquire a special symbolism and through them, they are integral parts of identifying the saints and the representations and give evidence of the life of the saints and the history of the representation.

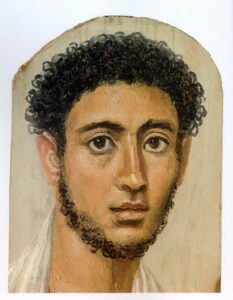

If one observes the figures depicted in Byzantine iconography, one will be able to perceive that the influences it has received are brought from Egypt and specifically from the portraits of the Fayum (1st-3rd century BC), whose art goes back in the Hellenistic years.

The Fayum were painted on portable material pieces (wood or cloth) and had a funerary use. They were originally hung in the house of the person depicted on them, until his death, and then placed on top of his embalmed body, inside the burial chamber.

Picture 1. Fayoum.

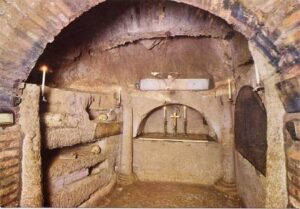

First we find the archaic iconography, which developed during the early Christian years (30-325 AD) and has to do purely with symbolism and thus with a didactic role. In this period, we do not hold back the artistic significance of the depictions, but rather the extent to which this symbolism of the motifs enhanced the religious feeling of the believers of the time. This period is also known as the “art of the catacombs”. Symbolic motifs such as the fish, the olive tree, the boat, the vine, etc. were used, influenced by pagan times.

Picture 2. Catacomb.

Then we have the Early Christian period (4th-7th century AD). It is the period of Constantine the Great and the transfer of the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome and the recognition of Christianity as the official religion of the state.

The theocratic state in these years, and after the persecution of Christians had now ceased, gives Byzantine art a significant change, which begins to differentiate itself in terms of its depictions. Painted depictions of the Saints and representations from the Old and New Testaments in frescoes and mosaics begin.

There would of course be a brake during the period of Iconoclasm (724-843 AD), where it was forbidden to depict human figures in paintings and art reverted back to decorative motifs of the animal and plant world.

During the reign of Theodora in 843 AD and by decision of the non-Ecumenical Council that took place in Constantinople, this period ended and the icons returned to their former use and of course their depiction, culminating in the Macedonian and Komnenian period (867-1204 AD) when Byzantine art was reborn.

The Seventh Ecumenical Council set the rules of Byzantine art in the decoration of churches and their iconography. The dogmatic, liturgical and historical (festive) are the three iconographic cycles in which the subjects of the iconography are now woven into the church with a defined iconographic cycle.

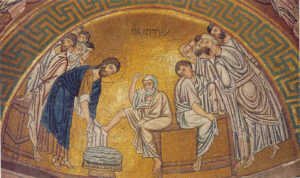

Finally we have the Late Byzantine period or Period of the Palaiologan period, which begins in 1261 and ends with the fall of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453. During this period, a flourishing and renewal of Byzantine art is observed.

In Byzantine art during this period, artists engaged in a naturalistic representation of the natural world, but also in capturing the emotional world in the forms, where the orthodox ethos, under the prism of a “spiritual realism” is captured through the pulse of life and the movement. There is richness of colour, strength in the drawing and the existence of the third dimension (depth) in the landscape and buildings.

Picture 3. Mosaic.

In the Turkish rule, the art of iconography slowly begins to fade away without any particularly characteristic work during these four centuries.

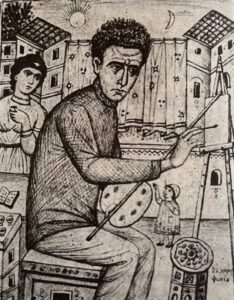

At the beginning of the 20th century, Fotis Kontoglou will try to breathe new life into the art of Byzantine iconography with great success.

There are two schools of iconography: The first is the Macedonian School, which was born in Constantinople, flourished mainly in Macedonia centered in Thessaloniki and influenced Serbia as well. Its characteristics are its realism and its freedom. It has brought rich colours, faces and clothes illuminated and possessed by movement. Its main representatives are Manuel Panselinos (13th cent.-14th cent.), Michael Astrapas and his brother Eutychios (the two painted icons in Serbia and flourished between 1294 AD-1317 AD), George Kalliergis (13th cent.-14th cent.) etc.

Picture 4. Macedonian School.

The second is the Cretan School. Byzantine iconography passed from Constantinople to Mystras (late 14th century), acquiring there a narrower character “given” to the Cretan School.

The original Cretan School was formed in Crete, after the fall of Byzantium (late 15th century – beginning of the 16th century). This School includes Byzantine idealism. Conservative, with restrained movements, austerity and nobility of face. The light is scarce, as if coming from some depth (element of deep devotion). The main representative of this school is Theofanis Kri (Heraklion 1490 AD – Heraklion 1559 AD).

Picture 5. Cretan School.

As the most important iconographers of both schools, we can indicate the following below:

- Saint Lazarus the Confessor. He lived during the time of the iconoclast king Theophilos.

- Saint Methodius Monk. He lived in the time of Justin II.

- Heraclides the Byzantium. He was born in Istanbul.

- Paul the museum curator. Mosaic painter.

- Stefanos Monk. He was a painter and a confessor.

- Andreas son of Artavasdou. He was an official iconographer during the time of Constantine Porphyrogenitus.

- Saint Alypios the illustrator, of Russian origin.

- Paul the iconographer. Unknown when he lived. Draw the image of Saint George on the horse.

- Michael Astrapas and Eutychios. He came from Thessaloniki and frescoed many churches in Serbia.

- Manuel Panselinos, one of the main representatives of the Macedonian School of the 14th century.

- Theophanes the Greek, iconographer of the 14th century and known for his work in Russia. He is considered the teacher of the great Russian iconographer Saint Andrei Rubliov.

- Saint Andreas Rubliof. He was born in Russia around 1360 AD. He is considered by all Russian painters as the main representative of ancient Russian art. The Holy Synod of the Russian Church officially recognized him as a saint in 1988.

- Nikolaos Ioannou and Kastrisios. They came from Kalambaka in Thessaly.

- Theophanes the Monk Chris. Leading icon painter of the 16th century and main representative of the Cretan School. His work was continued by his two sons.

- Antonius the Crier. Strict and simple iconographer, student of Theophanos of Crete. He lived in the 16th century. Iconographer of the Cretan School.

- Frankos Catalanos. He came from Thebes and is one of the best iconographers of the 16th century. His painting belongs to the Cretan School but also has influences from the West.

- George Priest and sacellar of Thebes. Mural painter.

- Andreas Ritzos, illustrator at the end of the 15th c. His works can be found in Italy and Patmos.

- Michael Damaskinos the Judge. Born around 1530 to 1535 AD. There are very few dated images of him. Iconographer and many of his works exist in Corfu (signed). He used Italian elements in his works and his influence on contemporary and later painters was very great.

- Holy Shepherd the Painter. He was born in Sofia, Bulgaria. In 1942 he was recognized as the patron saint of Bulgarian painters.

- Emmanuel Lampard (early 17th century). He painted only portable icons with influences from Palaeologian and early Cretan patterns.

- Saint Nilos the Myroblytis. He was born in Peloponnese.

- Aggelos o Cris, iconographer, who only made portable icons and lived at the beginning of the 17th century.

- Ieremias Palladas. He was a hieromonk and a famous icongrapher of his time. He followed the traditional style and rarely used Italian elements. He died before 1660 AD.

- Emmanuel Tzanes (Rethymnon around 1610 AD-Venice March 28, 1690 AD). Sometimes it follows the Byzantine models of the 14th and 15th centuries and sometimes it is inspired by Western works, sometimes following Flemish copper engravings.

- Konstantinos Kontarinis (18th century). He followed in many of his works the style of Fr. Emmanuel Tzane.

- Dionysios hieromonk from Fourna (1670 AD). He painted portable images, but also murals. He admired Panselinos and followed him in his style. He left behind him able disciples.

- George Markou. His hometown was Argos. He was a muralist. His students and their successors arrived almost until the end of the 18th century.

- Saint Savvas of Kalymnos. He was born in Iraklitsa in Eastern Thrace in 1862.

- Fotis Kontoglou. He was born in Kydonies (Aivali) in Asia Minor in 1895. In the 1950s-1960s he was at the peak of his iconographic activity and generally had a rich contribution to the field of art. He painted many portable icons and frescoed many temples. He is considered the regenerator of Orthodox Iconography. His students were Yannis Tsarouchis, Nikos Eggonopoulos, etc.

Picture 6. Fotis Kontoglou.

Today this art is flourishing in Greece and throughout the Orthodox world, where aspiring and talented young iconographers, men and women, with the use of new materials and technology, manage to continue to preserve the spirit and meaning of the term ”art”, because we must not forget, beyond its devotional-religious part, iconography is part of visual art.